So, Your Ancestor was a Civil War Soldier?

Searching for that Civil War Ancestor

Prisoners From the Front

by Winslow Homer 1866 Metropolitan Museum

Homer captures the appearance of soldiers of both sides.

Prisoners From the Front

by Winslow Homer 1866 Metropolitan Museum

Homer captures the appearance of soldiers of both sides.

I have both an interest in genealogy and a separate interest in American military history. I am a descendant of a Confederate trooper and the designated family historian for a surname organization. Recently, I have been combing the well-known commercial genealogical site Ancestry.com to spot errors in my family databases. Please be aware that many examples that I give in the following material are fictitious and only for the sake of example. There may or may not have been a John Smith in the 13th Ohio Infantry Regiment and so on.

|

So, how do you decide if a male of military age might have been a soldier? In some cases, that fact has been passed down in the family and it is just a question of documenting it. In other cases, you must delve for it. There are databases listing Civil War soldiers and if your person shows up on one that is a beginning. I should offer a word of caution here. If your ancestor was John Jacob Gingleheimer you may have it easy, assuming Gingleheimer is spelled correctly. On the other hand if he were named John Smith, I am sorry for you. You may find there were thousands of Civil War soldiers by that name. It is not uncommon to find multiple men with similar names living at the same time. I would say first that you should focus on the logical. If John Smith lived, died and was buried in Pennsylvania, he is not likely to be the man in the First Kansas Cavalry Regiment. If John Smith was a blacksmith, he was not likely to have been the surgeon of the 47th New York Infantry Regiment. If John Smith was killed in 1864 at Cold Harbor, he did not father your ancestor in 1872 and so on.

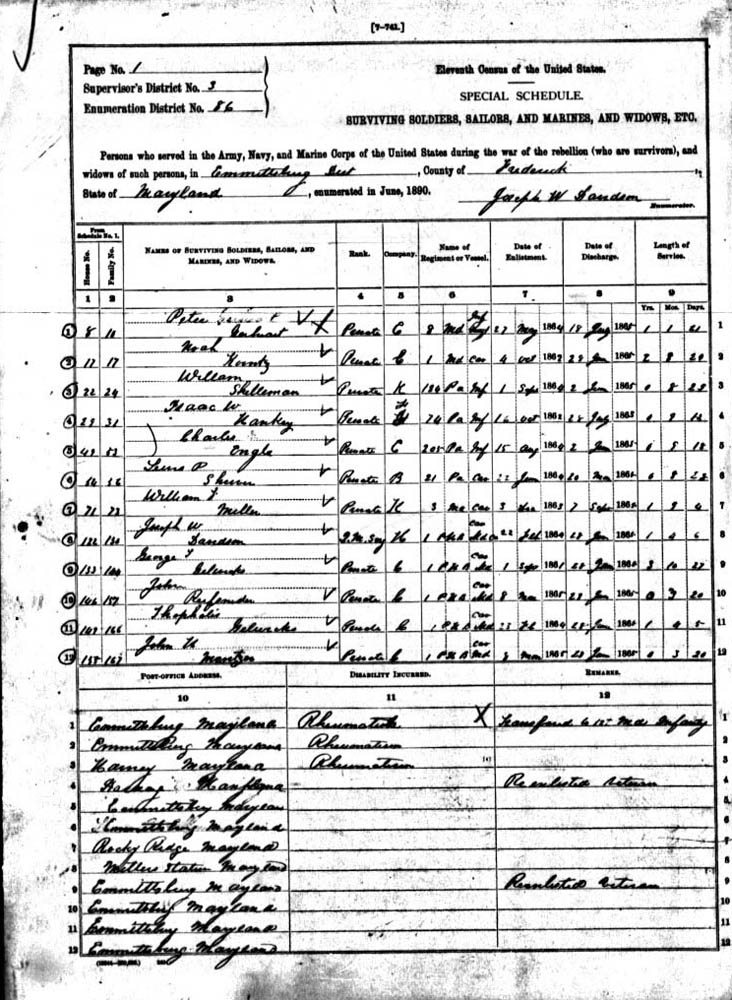

A Page from the 1890 Veteran's Schedules U.S. Census

Notice that the information is detailed and very helpful.

Okay, let us assume that we have your man. John Smith of Company A of the 13th Ohio Infantry Regiment. A key principle is that a soldier’s personal military history is generally reflected in the history of his unit. Let’s Google “13th Ohio Infantry Regiment.” We learn from a Wikipedia article that two units had that designation. The first was enlisted for 3 months of service and the second for three years of service. By reading the unit’s history we can learn of its movements, battle participation and assignments to larger units. You can assume that you ancestor was part of this but there is a possibility that he was absent for a block of time and not at a particular battle, etc. For this reason, it is important to document his date of enlistment and date of discharge. It also may be possible to document absences in between. You may be confused by several different dates given by the same or different databases as the enlistment date. Do not worry about it and pick the earliest among the several dates. That is most likely to be the date he signed on the line so to speak. While the unit was organizing there would have been an initial muster as a unit in state service and also an initial muster into Federal service and these dates sometimes appear as “enlistment date.”

The basic system of origination, method of recruitment and troop utilization in both the Union and Confederate Army was nearly identical and thus what is said about one is true of the other. This should be of little surprise since the higher officer corps of the Confederate Army were mostly men who resigned from the U.S. Army at the beginning of the war. There was even one officer, who was still serving in the U.S. Army at the Battle of First Manassas and only afterwards went South. A descendant of this man can honestly say that his ancestor fought on both sides, as can those who descend from “galvanized Yankees”, those Confederate POWs who agreed to serve in the U.S. Army in the West against hostile Native Americans. The Confederate Army was created in the image of the “Old Army.” Navy and Marine personnel are a special case and I must confess that I rarely have encountered any, but I am sure that genealogists whose ancestors lived in coastal communities with strong seafaring traditions might expect to find a few. Both the U.S. and C.S. Marine Corps remained small and in a traditional shipboard role without any particularly memorable moments. The vast majority of Civil War ground troops were members of one of three Army combat arms: Artillery, Cavalry and Infantry. Today, these men are the tip of the spear and there are large numbers of logistical and support personnel backing them up. In the Civil War that was not the case. There were very few specialized logistical units, such as, dedicated engineer, medical or signal troops. If men were needed for those functions they were often detailed from line units for periods of time.

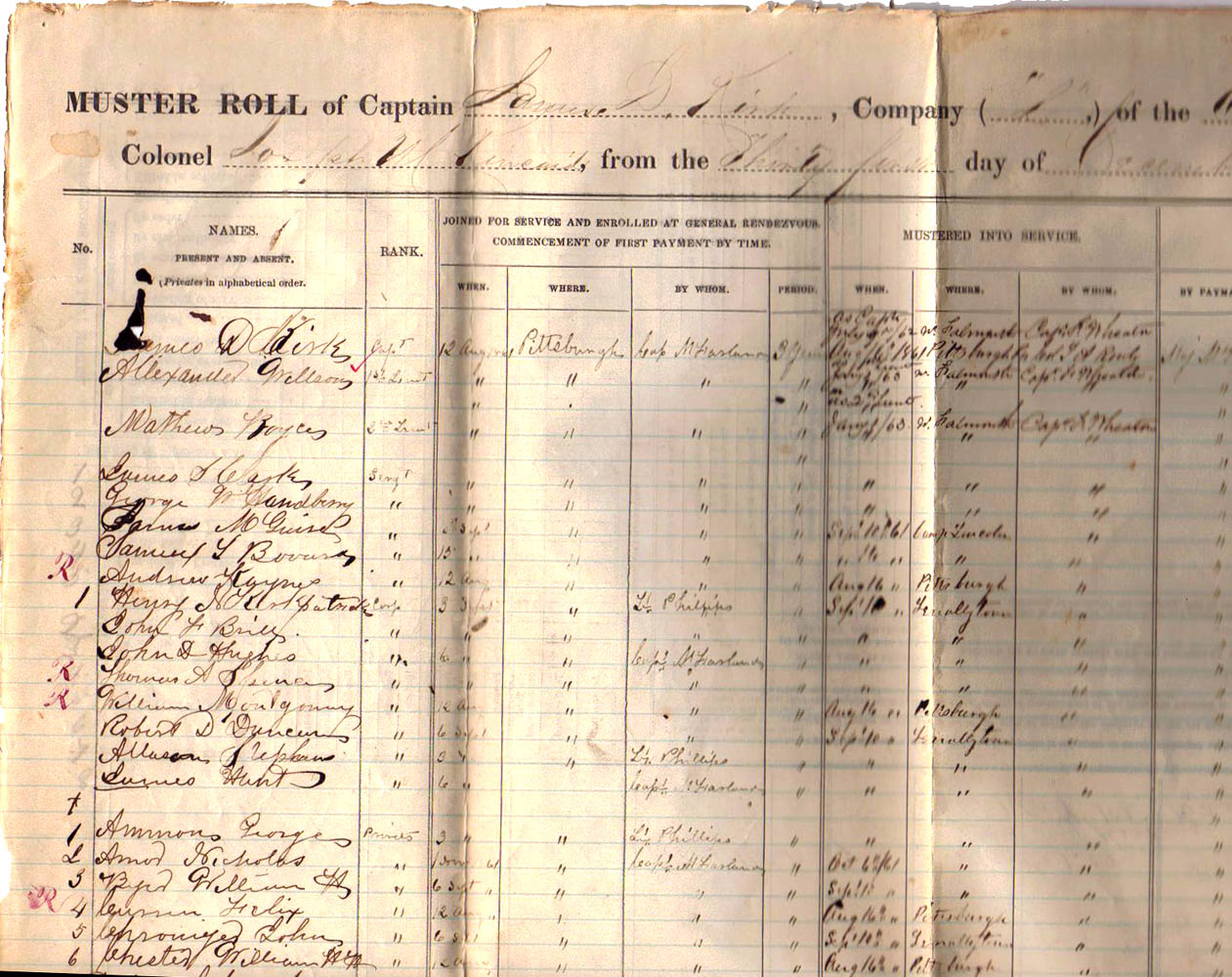

Most Civil War soldiers were members of the infantry branch. The basic unit was the infantry regiment. The title of most regiments includes the name of the state that was responsible for recruiting and training the unit; for example, 20th Maine Infantry Regiment. At various points in the war states were assigned a quota of troops to provide for service of the United States. Once the state was ready with the regiment, it was mustered into U.S. service and at that point the Federal government provided for it until the regiment was mustered out of service at the completion of its term of service or the end of the war. There were units which did not have a state designator. Units of the Regular Army of the United States, U.S. Sharpshooters and U.S. Colored Troops did not. Regiments were commanded by a colonel. He was assisted by a regimental staff, which included a small number of other field officers (a lieutenant colonel and major), surgeon and assistant surgeon, adjutant, quartermaster, regimental sergeant major and band members, etc.

I have a word of caution regarding terminology used in some of these Civil War databases, including those in Ancestry.com. The person who originally set the titles of these data fields was very uninformed regarding Civil War military terminology, which is a shame. Members of the regimental staff and field are referred to as being members of “Company S.” This is totally bogus and there never was such a thing as “Company S.” These particular soldiers were members of the regiment, who were unassigned to a particular company. All the other soldiers of a regiment were members of one of its 10 companies, which were lettered A to K with the letter J omitted because it might be taken for an I. Companies were commanded by a captain, who was assisted by one first lieutenant and one second lieutenant. You can think of a regiment at full strength as being about 1000 men and a company about 100 but they were almost never at full strength. Veterans had a strong affiliation toward their regiment and regiment name is a basic fact that genealogists recording information about a soldier should state. If you tell any Civil War buff that your ancestor was a Civil War soldier, you can expect the question back, “Oh, what regiment?” The regiments were grouped into larger units: brigades, divisions, army corps and armies. These might change during the war with various reorganizations, etc.

|

|

I have some comments about Civil War ranks. The primary division is between officers and enlisted men. Enlisted men, basically privates, corporals and sergeants, were the foundation of the army and were enlisted for a term of service, which was different for different regiments. During that time the soldier must serve and legally would not leave the service without some situation causing the Army to discharge him prematurely. In those cases in which you discover a soldier was mustered out prior to the muster out date of his regiment expect to find some explanation. It might be disability on a “surgeon’s certificate” or to take a commission as an officer or some other reason. Sometimes it is not clear from available searchable records why and you must get copies of the soldier’s files from the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). Those are rather costly and I do it only when I absolutely must. I must say that when I do I really develop a new appreciation for the soldier as an individual, particularly after reading the pension part of the record. Most veterans who lived long enough got a pension but there might not be pension records for a particular man.

Things were much different for officers. They were supposed to be gentlemen and the natural leaders of society according to 19th century notions. Of course, many proved to be “dammed fools” or alcoholics or worse but at least they managed to maintain the dignity of a gentleman long enough to procure a commission. A researcher should avoid saying that an officer enlisted. Enlisted men enlist. Officers are commissioned. Unlike enlisted men officers can tender a resignation at any point in time and if accepted can leave the service. A lot of the older men who became officers early in the war suffered a breakdown in their health from field conditions and emotional strain and resigned prior to their unit being mustered out.

|

There also were brevet ranks during the Civil War. If your ancestor received a brevet rank, it is worth documenting and it may explain why a man that was only lieutenant colonel was photographed in the uniform of a brigadier general and was addressed after the war as general. These were honorary and not substantive ranks. The full story of the rise and fall of brevet ranks in the U.S. Army is really very interesting but I do not have space to do so in this discussion. I find it confusing to call an ancestor “General So and So” when he truly served only as a field officer during the war. Most of these brevets were awarded after the war and post-dated to a date during the war. The typical date is 13th of March 1865, which became known as “the Glorious 13th March 1865” and not because anything happened but because the system of deciding who got a brevet and who did not had become so politicized in the postwar era. The existence of these brevet ranks can be confusing to a researcher when first encountering them.

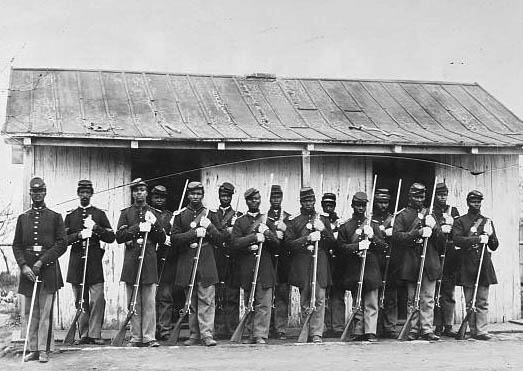

These soldiers were recruited in Kentucky in 1864 and photographed at Fort Corcoran, Arlington, Virginia in 1865. They are wearing their dress uniform with frock coats, white gloves and brass shoulder scales. The soldier at the extreme left is a non-commissioned officer but his chevrons are not well seen in the photograph. He is holding a non-commissioned officer's sword and wearing a sword belt buckle unlike the other soldiers. All in all they are a very spit and polished group.

|

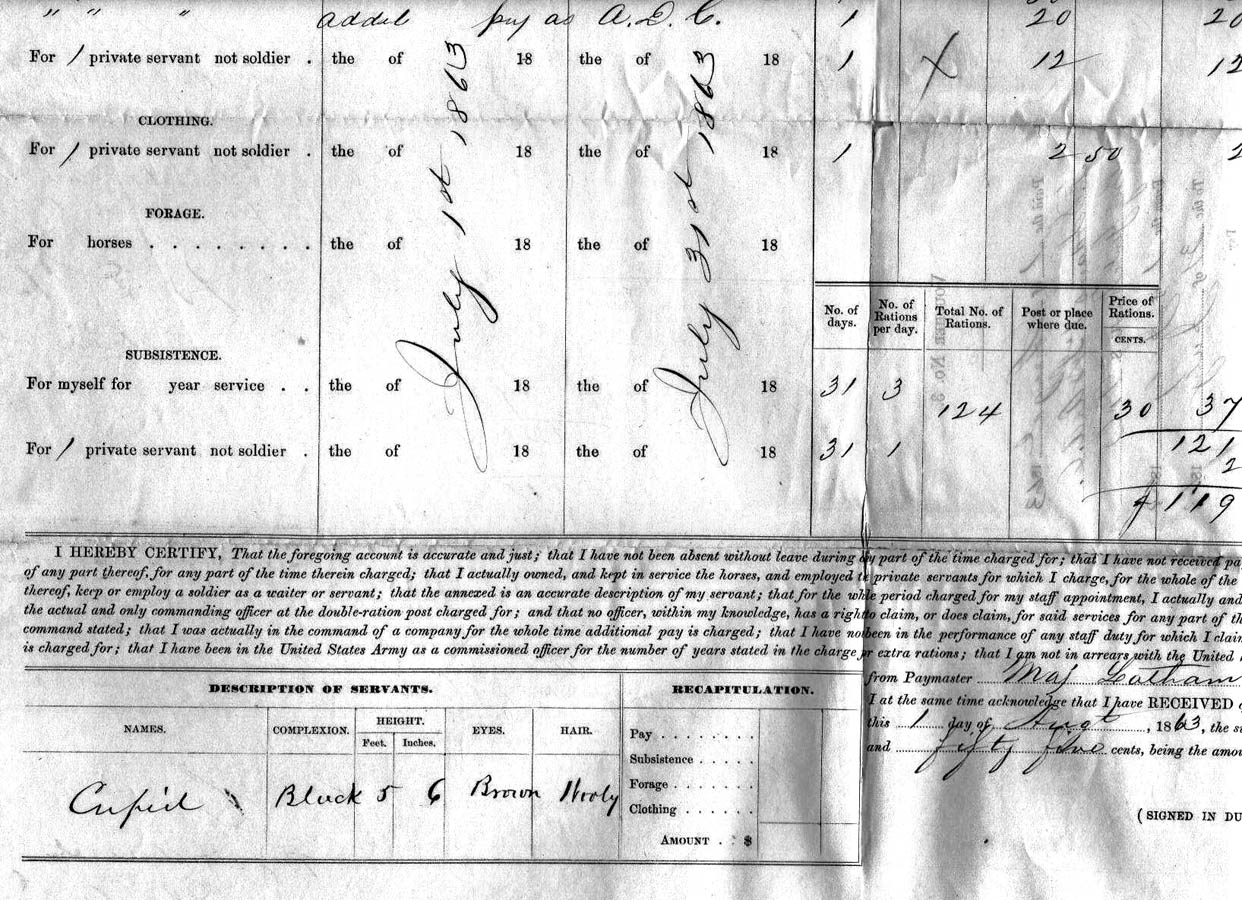

Adams employed a civilian African-American servant named "Cupid." It is likely this is a nickname and does not reflect the identity of the man. It was accepted that a gentleman needed a servant but unacceptable for a soldier to act in that capacity in the U.S. Army. The existence in the field of these black officer's servants is frequently mentioned in period accounts. Their duties included procuring and preparing meals (officers were not entitled to Army rations) , caring for uniforms, equipment and horses, etc. They were known for their resourcefulness and it is sad that it is nearly impossible to document who they were.

Another group I would mention are foreign-born individuals. Their records should be there just like native-born, but often the name is so butchered you will never recognize it and often as a genealogist you may have no idea just were your ancestor was living during that critical period just after his arrival. I can only say there were large numbers of recent immigrants in the Union Army and it is not easy to know what became of them after the war.

|

Some women openly were associated with troops, but they cannot be called soldiers. The well-known, Medal of Honor recipient Dr. Mary Edwards Walker was a civilian contract surgeon even if she affected an officer’s uniform (try that today). I am uncertain of the official status of the female Vivandičres in Zouave regiments, but I am certain they were never mustered into U.S. service as soldiers. The contributions of female civilian, noncombatants to the war effort were huge, but this discussion is about Civil War soldiers. I should also acknowledge as under-appreciated, the fact that the Civil War unleashed forces that would lead women to a more active and militant role in the body politic, but that is the meat of a discussion far beyond this one.

Having explained the nature of the military structure during the Civil War I am next going to discuss the various resources that are available to researchers.

|

|

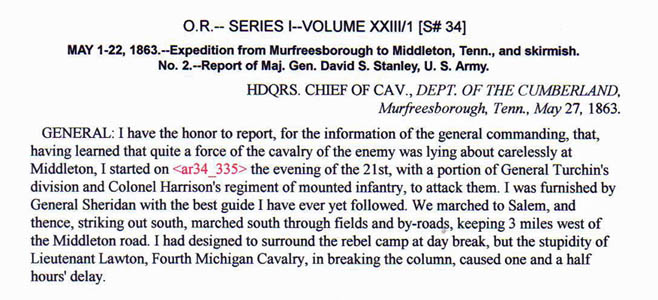

Another general source that can provide information is the series The Official Records of the War of the Rebellion. These are often cited as the Official Records or ORs. The original publication consisted of 70 volumes grouped in four series, published between 1881 and 1901. They are mostly a collection of original reports written by officers of both sides. Modern technology allows them to be searchable on key words. They are available on-line and I own a CD of them. You are unlikely to find a particular enlisted soldier mentioned, but regiments certainly will be mentioned and the commanders of units often recount their version of what happened to your ancestor’s unit during a particular battle and that is always interesting to read by way of a deeper understanding of an ancestor’s experience. I like the ORs as a source but there is a learning curve to use them effectively. There is a lot of material but often it is well buried.

Major General David Stanley blames a subordinate, Second Lieutenant George W. Lawton, for the failure of an operation and uses the word "stupidity" in describing his actions. These reports were written often in a self-serving manner to make the commander look good and should not be read as an unbiased record of events. Still reading something, such as this, might explain why the promising career of Lieutenant Lawton suddenly took a nose drive.

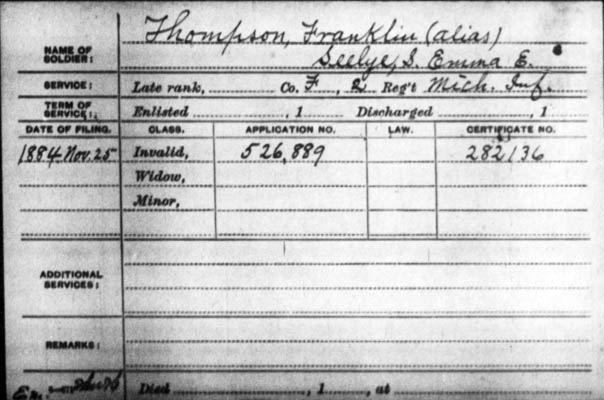

Ancestry.com (proprietary site with an annual fee) has a collection of military records that are searchable. There are several different databases listing Civil War Soldiers and sometimes you will find your man in one and not another. If you ignore the previously mentioned terminology problems, the database that has the most information is called Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles, 1861-1865. That one often lists unit name and the dates of enlistment and discharge. Those dates are critical to establishing what a soldier might have done while in the unit. Other lists have approximate age and residence prior to enlistment. That kind of information might help you decide if you have the correct person, but the ages given are often wrong. I am usually able to get enough data from Ancestry that I can successfully fill out NARA’s NATF Form 86.

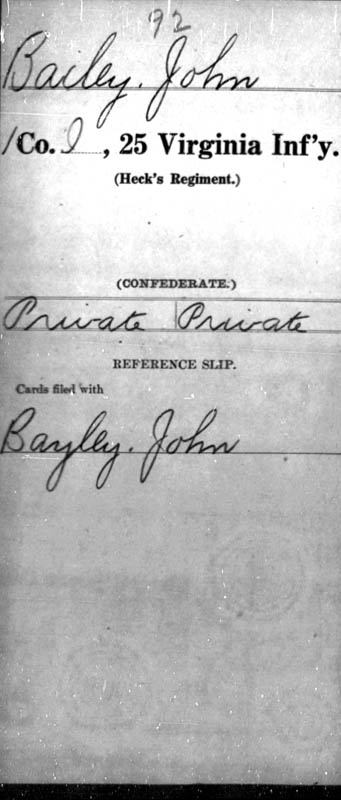

Fold-3 is another proprietary site with annual fee. They have a special focus on military records. A lot of their material exists in other places but having a focus on military records there are many cases in which Fold-3 allows you to view original documents not otherwise available on-line. In certain cases you can avoid paying the rather steep NARA fees and view the complete service record on-line. However, this is not consistent for all soldiers and in some cases all you get is the disappointing “General Index Card.” I find Fold-3 very hard to navigate. I keep telling myself that they could have designed it in a more user-friendly fashion. They have a tutorial that should explain how to use it effectively but in my mind a well-designed, user friendly site should not need one. What I have figured out after months of struggle is that when you are looking for a given soldier; for example, the John Smith who as in the 13th Ohio Infantry you must go through a process to focus your search. The key operation to bore down on what you want is to right click on it and ask that the data “Open in a New Widow.” First you will need to have stipulated John Smith in the Civil War and then all the John Smith soldiers from Ohio before hitting the listing of that one John Smith in the 13th, doing that right click and “New Window" all the time. Otherwise you seem to be stuck with 600 irrelevant hits, including every other John Smith on both sides of the conflict and then things seem to refuse to open even if you find what you want. I am certain Fold-3 designers would argue with what I say but this is my experience and I am not really looking to be critical.

There are all kinds of rosters, large and small. Some are available on-line and others in print form. Some that were originally in print form are available now on-line. Google Books or other similar formats have made older, now public domain books searchable on-line. I must confess that this development still leaves me a little in awe because I can now do in minutes what might have taken me an afternoon in a research library in the past. The major problem facing a genealogist using a roster is the question is a man with the same name as my person of interest in fact him? The National Park Service has an on-line roster called The Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System” (CWSS) which is a database containing information about the men who served in the Union and Confederate armies during the Civil War. However, it provides only minimal information, namely the name of the regiment that the man served in. My favorite on-line general roster is the one of Ancestry's that is called Civil War Soldiers 1861-1865 Records and Profiles that I mentioned before. This is the work of an organization called Historical Data Systems Inc. of Kingston, MA, and is actually a compilation of various older, published rosters into a single source. It often will provide enlistment and discharge dates, which I consider critical elements of a soldier’s service time-line. In print there is the 16-volume The Roster of Confederate Soldiers 1861-1865 by Broadfoot Publishing of Wendell, NC. However, this appears to be missing Confederate soldiers in units from Border States. Other rosters are state specific and some of these were originally published under the aegis of the state governments. For example, Maryland and Ohio have very nice compilations for their Union veterans. Other rosters appear as appendices in unit histories. The Virginia Regimental Series published by H. E. Howard Inc., of Lynchburg, Virginia includes rosters of soldiers in each unit written by local historians and often with supplemental information about the soldier.

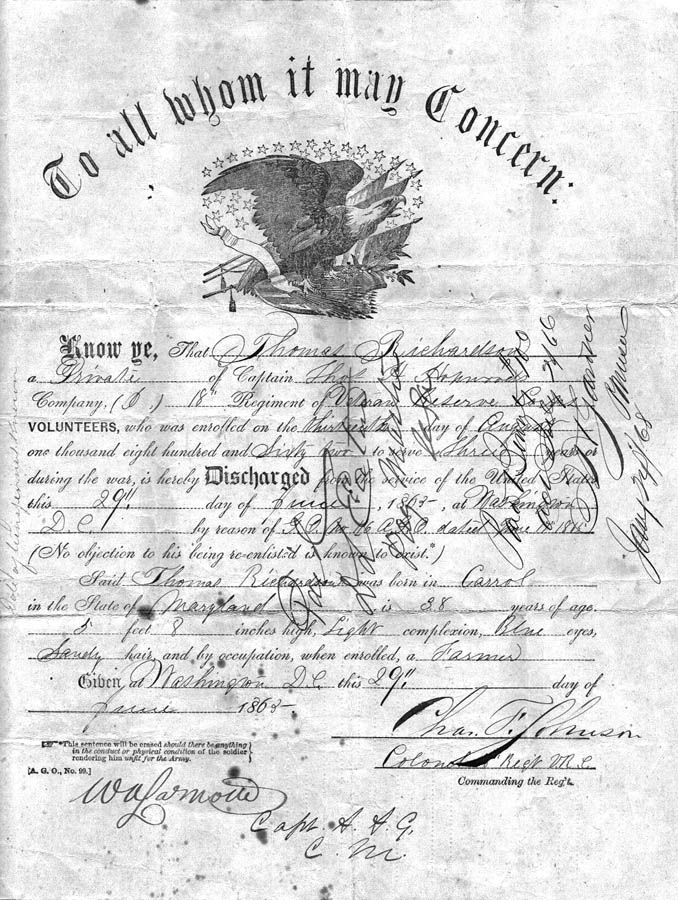

Richardson, a native of Carroll County, Maryland, originally enlisted in Company E of the 4th Maryland Infantry and was injured on the march and transferred to the 18th Regiment Veteran Reserve Corps. The compiled service record should reflect this information but the original document would have been in the veteran's possession.

It is said that the Civil War was one of the most written about events in history. I have already said that a soldier’s history is generally the history of his unit. There are numerous published unit histories. I might say that it would be unusual not to find one for any of the units that served for a period of time. A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion by Frederick H. Dyer (1908) is a roster of Civil War Units and contains a thumb nail sketch of each. Dyer’s material is commonly available on-line to the point that when searching for background on units, I find myself reading it over and over at site after site and I wonder if anyone troubles themselves to write anything that is original. More selective is a source called Regimental Losses in the American Civil War, 1861-1865 by William F. Fox (1889). If your ancestor’s unit was a 3-month regiment that guarded bridges in Tennessee do not expect to find it. However, if it was a well-known and hard-fought unit Fox breaks down its casualties by company and battle. In addition to these two sources, there is another unique three volume reference series called Regimental Publications and Personal Narratives of the Civil War: A Check List by C. E. Dornbusch of the New York Public Library (1961). An Additional forth volume was published in 1987 by Robert K. Krick and then revised and updated in 2001 by Silas Felton. This is a great source and can guide you to books that will help you live your ancestor’s experience. Once you know the title that you are looking for you may be able to purchase a reprint or acquire a book via inter-library loan. I once got a long out of print Civil War book by inter-library loan. When I opened the book up I was shocked to read on the fly leaf “Ex Libris John Milton Hay.” This man was Abraham Lincoln’s private secretary and later United States Secretary of State. I asked a friend who was a museum curator why they would circulate a volume that belonged to such a well-know historical figure. His reply was that librarians are all about the book and really do not consider the history of a particular volume. If you are wondering, I did return it when due. I should also mention Francis B. Heitman's Historical Register and Dictionary of the United States Army (1903). This is particularly useful as a source for officers of the Regular Army but does include some material on the state affiliated volunteers as well.

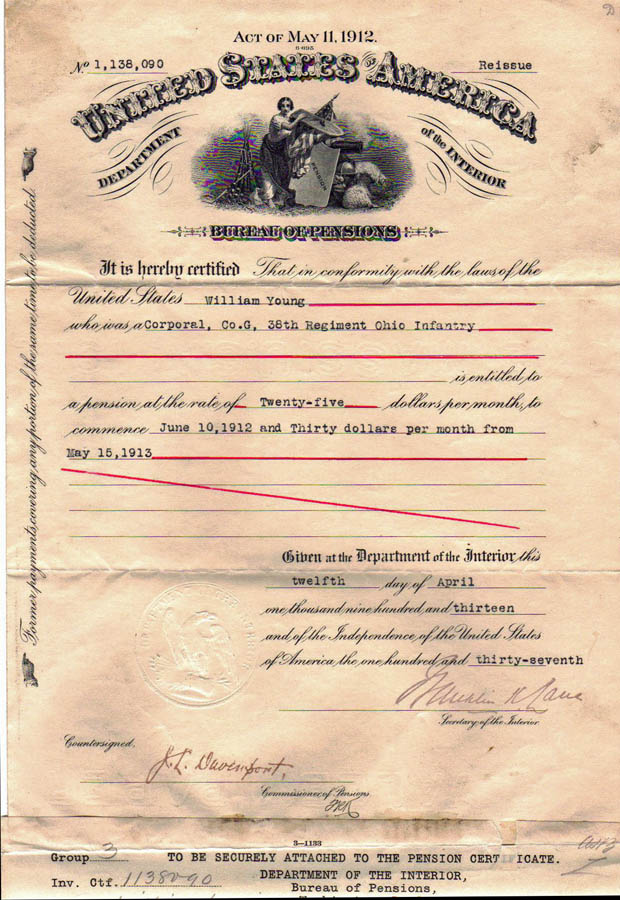

Young had already been pensioned and this certificate reflects a raise in the monthly payment under the Act of May 11, 1912. The original document would have been in the veteran's possession.

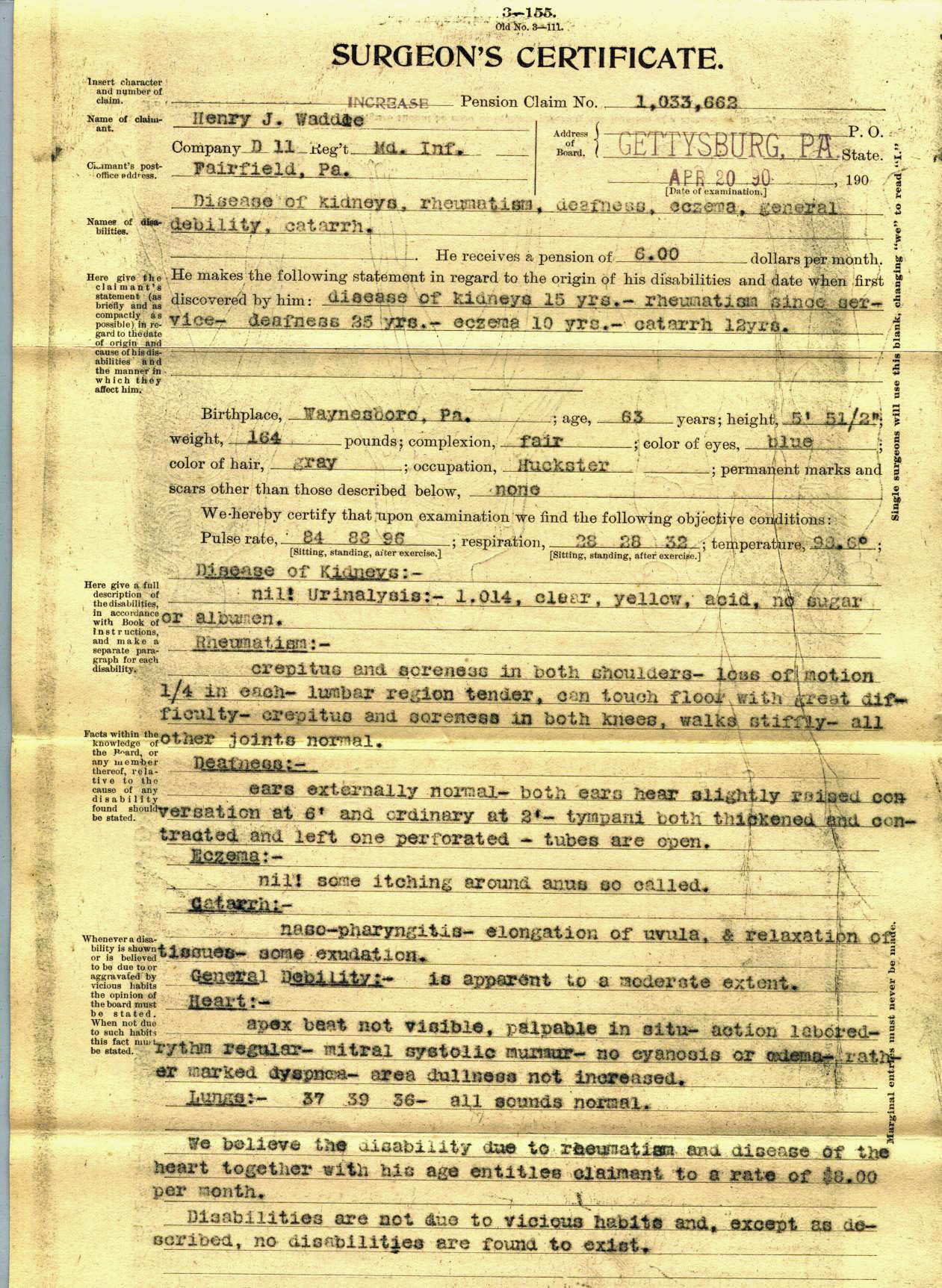

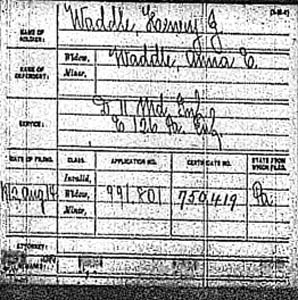

The older pension acts required that a veteran be disabled or an invalid. Almost all these documents list a host of conditions.

|

Millions of soldiers' photographs were taken during the Civil War. It is always exciting to find one of any ancestor and doubly so for one of a soldier in uniform. Some photo archives have collections of images of individual soldiers, including the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center at Carlisle, PA. Many others are in private hands. One big problem with images is the issue of who owns them and do you have permission to reproduce them? Certainly if you plan to reproduce or publish an image you should make a good faith effort to have permission to do so. I was once advised by a lawyer that even though I owned the photo in question, it was really the intellectual property of the long-dead photographer and in order to publish it I should trace and receive written permission from each and every modern descendant of the man. Of course, that is unrealistic to the point of crazy but is emblematic of those vested interests in our society who would profit if there was never such a thing as fair use or public domain.

|

|

|

The photographs pictured are called carte de viste or (CDVs). These were taken with a camera that made multiple copies. Soldiers handed out the copies to family and friends. They were often kept in albums. It is possible to extract information from a photograph. The first photograph is an unidentified member of the 9th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment. Early in the war the clothing stocks at the various Army depots were exhausted and the Federal government asked the states to take responsibility for the initial uniform issue. The men of the 9th received a distinctive, state-issued uniform, which this man is wearing. In addition, the hats have a number 9 surrounded by a wreath. The photo of George F. Thomson shows him wearing a typical single-breasted officer's frock coat , appropriate for an assistant surgeon whose rank was equivalent to a first lieutenant, and holding a kepi with the regulation U.S. in a wreath. Chaplain Father Thomas Quinn is wearing a distinctive Rhode Island smock and captain's shoulder straps. Chaplains were not considered officers by the Army and most did not wear shoulder straps. However, they were allowed pay equivalent to a captain of cavalry and the occasional chaplain did wear captain's shoulder straps. Quinn served in several different Rhode Island units until he was discharged from the Army as a supernumerary in January 1862. At that time his was with the 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery and what we now call the tables of organization did not call for a light artillery unit to have a chaplain. During the war several chaplains were mistaken for a combatant and shot because they were wearing what appeared to be an officer's uniform. That is exactly what Quinn was doing in his photo.

I have a plea regarding photographs in general. If you look on E-bay or go to your local antique mall, you will find piles of 19th century photographs of unidentified individuals, including those of Civil War soldiers. These were once someone's relatives and yet the identities of these individuals are now lost forever. If you own a photo and know the identity gently write the name in pencil on the back. Otherwise, in 50 years time it to may join the army of the unknowns that some antiques dealer will will tell you was "bought at an estate sale."

|

Of course, there is much more that I could have said and sources that I could have mentioned. As a fellow genealogist I respect the fact that this is your search and people learn by the experience of doing. Please document where you find information. Five years from now you might not remember. It is always exciting to find an ancestor that you can tie to a historical event, such as the American Civil War, but let us never forget for all its drama this was a tragedy of the highest magnitude. The American political system is founded on the ability to reach compromise and the issue of the existence of slavery did not lend itself to compromise. Instead we suffered a disastrous Civil War. I hope it was a lesson well-learned and yet today I observe an unwillingness to have polite political discourse and to reach compromise. I hope that our ancestors do not judge our foolishness too harshly.

|

|

|

Above is group of three artifacts attributed to Captain Lovell Purdy, Jr. of Company H, 74th New York Infantry Regiment. The 74th New York was part of the Excelsior Brigade and Daniel Sickles' Third Army Corps and was present at Gettysburg. Acting against orders, Sickles repositioned his Corps forward of the Army of Potomac's battle line on Cemetery Hill and directly in the path of Confederate General Longstreet's attack on the Union right flank. Purdy was wounded and the 3rd Corps cut to pieces as a result. However, they did act as a "bumper" for the rest of the Union Army and the Confederate attack lost its momentum at Little Round Top. At this point three of the seven Union Corps had been smashed by Confederates attacks and R. E. Lee was confident of victory. The stage was set for Pickett's Charge. The outcome at Gettysburg was a near thing and either side might have won. Purdy was a witness to the events.