So, You Think You Love Horses?

Some Reflections on the Nature of Horses and Man

More Discussions by “The Accidental Horseman”

Parasites and Horses

When we use the word parasite we immediately think of internal parasites (endoparasites) and particularly worms, but in biology parasitism is understood more broadly as any kind of non-mutual relationship between organisms of different species in which, the parasite, benefits at the expense of the host. Often we think of a parasite as a ‘lower” organism but using the broader definition a vertebrate like the cuckoo or the cowbird practice a form of parasitism by virtue of their behavior of substituting their own eggs for the eggs of birds of different species. Parasites can range the animal kingdom from viruses to vertebrates. Generally, predation is not considered as parasitism. An effective parasite need not kill its host to exploit it. Complications of severe parasitism can weaken a host sufficiently to cause its death. Parasites are in their own way highly evolved and specialized in their missions of infesting their hosts. They often have very complicated life cycles and different stages of development involving additional organisms. In truth, if they were themselves capable of such thoughts they might think of us as their "hosts" as being the "lower organism."

Organisms that infest the surface coat of horses are called external parasites (ectoparasites). These might include mites and ticks as examples. However, for this discussion I will focus on the internal parasites. Lest we forget all animal species, including man, have parasites, but ground feeders such as horses are particularly vulnerable to them. In the wild horses move on and do not gaze long in areas with fresh manure. The domestic horse is more vulnerable enclosed in smaller areas. However, horses generally will avoid eating in areas where they defecate. One danger is that we do not see what is going on inside of a horse and may miss signs of parasitic infestation, all leading to complacency. However, parasites are nothing to be complacent about. They may be small but they need to be taken seriously.

The internal parasites (endoparasites) of Horses:

Large Strongyloid

|

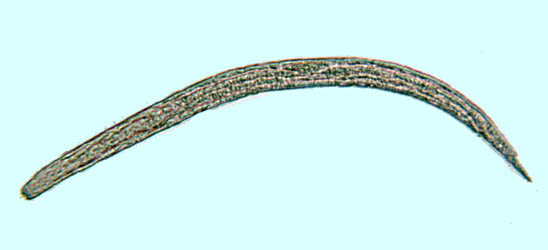

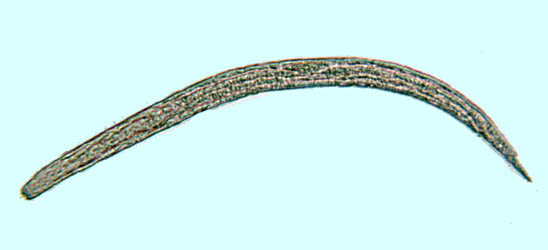

- Large Strongyloids (Large Redworms of Strongylus and Tridontophorus Species)

The adults of these worms may be as large as two inches. Their eggs are expelled with feces and the horse acquires them while grazing. The eggs hatch in as little as three days and the larvae of the Strongylus species penetrate the wall of the intestine and can migrate into arteries and other organs. This can cause thrombosis and ischemia to the bowels leading to symptoms that resemble common colic.

Small Strongyloid

|

- Small Strongyloids (Small Redworms Nematode Species)

The adults of these worms are generally under an inch in size. Their eggs are also expelled with feces but the larvae develop in the environment and are they are ingested. They are better tolerated by the host but also more numerous than other parasites. A large burden of worms can cause anemia and weight loss.

Pinworm

|

- Oxyuris epui (Horse Pinworm)

The eggs of this species are deposited at the opening of the horse’s anus by the female worm, which can be about five inches long. The eggs contaminate the environment and are ingested by the same or other horses. The eggs around the anus cause irritation and animals with infestations often rub their posteriors on the sides of buildings and fences causing sores.

- Ascarids (Round Worms)

You might think all worms are round (some are flat) but the Ascarids, represented by Parascaris equorum, are particularly bad actors. It is said that their eggs can survive being submerged in formaldehyde. They are also big, up to twenty inches long. Like other parasites the eggs are passed in the feces but Ascarids are very resistant to drying. The larvae develop still in the egg and hatch once ingested. They then go into the intestine to the circulatory system and in time migrate to the lungs from which they are coughed up and swallowing. All and all it is a grand tour of the equine body with much potential harm done to the animal on the way.

- Trichostrongylus axei (Stomach Hairworm)

These are small thin worms that measure only about one-quarter inches. They like warm humid conditions and a heavy infestation can bloody diarrhea and anemia. Foals are particularly at risk.

- Habronema Species (Large-Mouthed Stomach Worms)

These adult worms can get as big as eight inches and have a secondary host in the stable fly, which ingests them on horse manure. The larvae develop in maggots and move from the adult fly to the horse when the fly lands at a suitable somewhat moist location on the horse’s body, including the nostrils, lips and wounds. When they are swallowed they become adults in the horse’s stomach. The larvae can infest the horse’s skin and cause summer sores.

- Cestoda (Tapeworms)

Tapeworms may be the poster child of the parasite family and perhaps the first one we think of. There are several species that infest horses and these can measure up to about two and one-half feet long. Many Cestodes have scolex or hooks that attach to the intestine wall but not the various equine species, whose scientific names are Anoplocephala magna, A. perfoliata and Paranoplocephala mamillana. They are highly evolved or maybe I should say devolved because they have totally lost their own digestive tract. They absorb nutrition directly through the body wall. They also do not concern themselves with male and female because they are both. Even better they exist in self contained segments in a long ribbon. Lose one of these segments downstream and no big deal there are many to spare. These segments produce prodigious amounts of eggs, which are ingested by a type of small oridatid mite that lives in soil. While grazing horses ingest the mite and the cycle of infestation continues.

- Dictyocaulus arnfieldi (Lungworm)

Lungworms are a major issue on donkeys and only occasionally infest horses.

Bot Fly

|

|

|

A Bot Larvae

|

|

|

Bot Eggs on a Horse's Leg

|

|

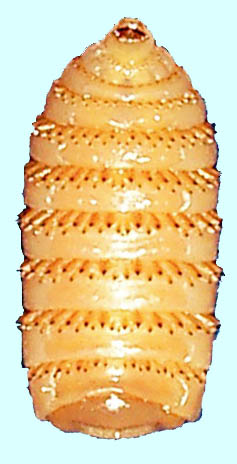

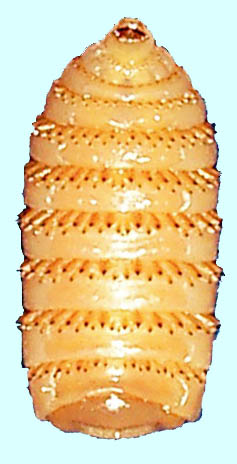

- Gastrophilus intestinalis (Bot Flies)

Bots are not a worm but an insect. The adult form is a fly. The female fly deposits her eggs on horse’s coat, particularly the legs and abdomen. You can see this happening but the bot fly is very fast and hard to swat. They appear more a wasp than a fly in action. The eggs are visible to the naked eye as a small yellow speck attached to an individual hair. The horse ingests them when it licks or bites the spot where the eggs have been laid. The fly is programmed only to lay in those spots were the horse is likely to lick and when you think about it nature never fails to amaze. The larvae (maggots are a type of larvae of some fly species and are familiar to most people) of the fly first inhabit the month and then migrate to the stomach lining where they spend the winter. In the spring they pass through the intestinal tract and leave the feces to live in soil from which they emerge as mature flies. I saw a lot of bot flies and their eggs when we boarded our horse but now I cannot remember the last one that I saw. I think modern wormers and a smaller herd makes them easier to control.

Controlling parasites is important to maintain heath of horses. Almost all horses live in environments where parasitism is a given. Prevention with regularly scheduled doses of antihelminitcs (a chemical wormer) is a reasonable approach. Historically, many horses were feed tobacco for this purpose. I also remember when we were dependent on our veterinarian to tube worm our horses. Putting a tube into the stomach to introduce the antihelminitc was rather traumatic to the horse-veterinarian interpersonal relationship as best I recall. Today we have better means that avoid passing a tube. A commonly used product is daily pyrantel tartrate added to feed, which kills large and small Strongyles, Pinworms, Ascarids, and many others. We supplement this with a twice yearly dose of the paste wormer, Invermectin. This kills large-mouthed stomach worms, stomach hairworms, lungworms and importantly bots and also many of the parasite species also killed by pyrantel tartrate. The overlap affords a global protection and prevents a huge parasite burden. There are situations, particularly in neglected horses or symptomatic horses where it is best to turn to a veterinarian for treatment and diagnosis. Diagnosis depends on a stool sample and identification of the specific egg types deposited in the feces. Treatment can be tricky since a massive die off of parasites itself can product serious symptoms in the host.

Most people are aware of the problem of adding antibiotics to animal feed. It produces short term gains for the producer but encourages the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria that effect the community at large. Since bacteria have a short generation time of about 20 minutes and exist in the millions in animals' bowels, evolution can work very rapidly to produce drug-resistant strains. What is less appreciated is that the same problem exists with prophylaxis against parasites with antihelminitcs. Although worms do not exist in the number that bacteria do and have a longer generation time, antihelminitc-resistant parasites have emerged in some herds in both the Americas and Europe. It may be that a new more targeted approach is needed but as yet no clear consensus has emerged among thought leaders in the field.

Yours truly,

The Accidental Horseman.

Back to Additional Discussions

Links to Other Sites regarding Horses

Back to Index Page