A Brief History of United States Cavalry

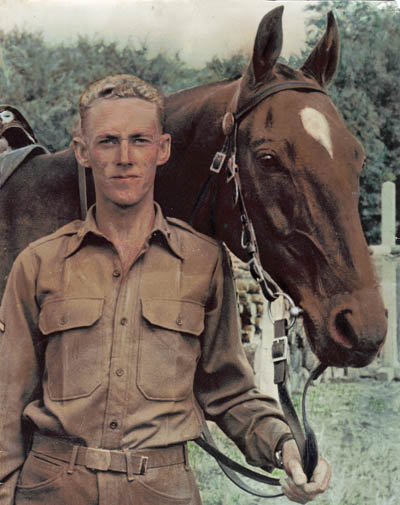

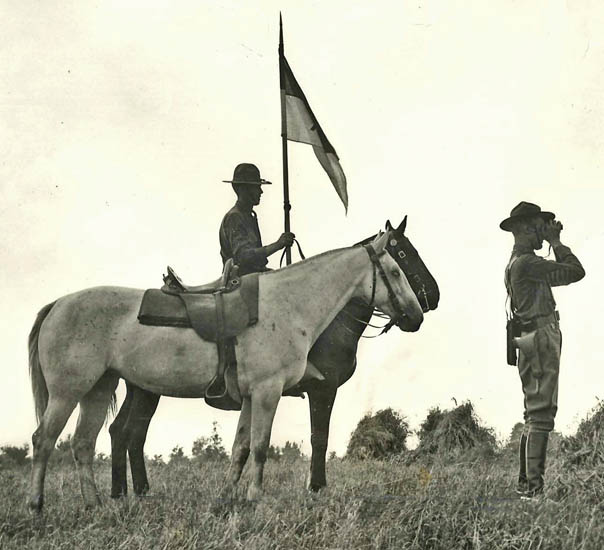

Two Warriors: A Private First Class and his Mount

Notice the McClellan Saddle

The United States raised cavalry units for service during the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. Because of the great expense in maintaining mounted units these were not retained in the service afterwards and no longstanding traditions developed around them. In the forested lands of the East and where travel by river was common, mounted troops were not seen as having any advantages over ordinary infantry.

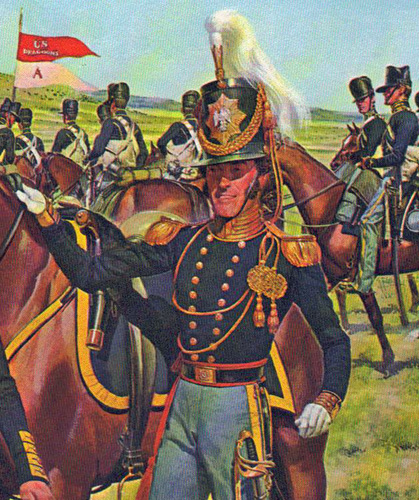

Dragoon Cap Plate 1833

|

|

Dragoon Officer 1836

By H. Charles McBarron

|

|

Prior to 1832 the only mounted units that served with the U.S. Army were state militia units who were called up for brief tours of service during emergencies. These units were limited to 90-days of service by law and lacked the skills and training needed to function as first class cavalry units. Once the plains became more populated the lack of mobility of infantry became a problem and in June of 1832 Congress approved a Battalion of Mounted Rangers. This experiment proved successful, and on March 2, 1833 Congress authorized a larger unit which this time was called The Regiment of U.S. Dragoons. Most European armies had dragoons, who were originally mounted infantry and structured and trained similarly to infantry units. Over time they evolved towards being light cavalry and Congress may have not been particular in its choice of the word “Dragoon” rather than “Cavalry” in naming the unit. Additional regiments of mounted troops were approved in the following years including one named the Regiment of Mounted Riflemen who were armed with the Model 1841 rifle rather than the more common musket of the period.

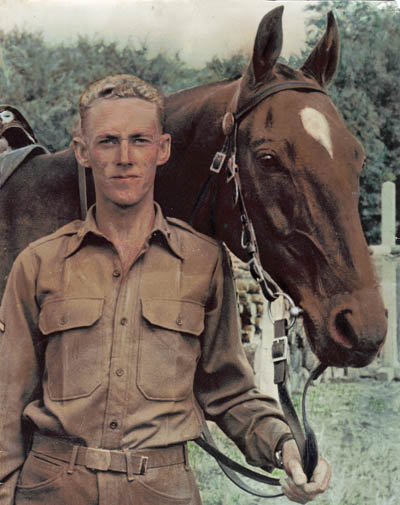

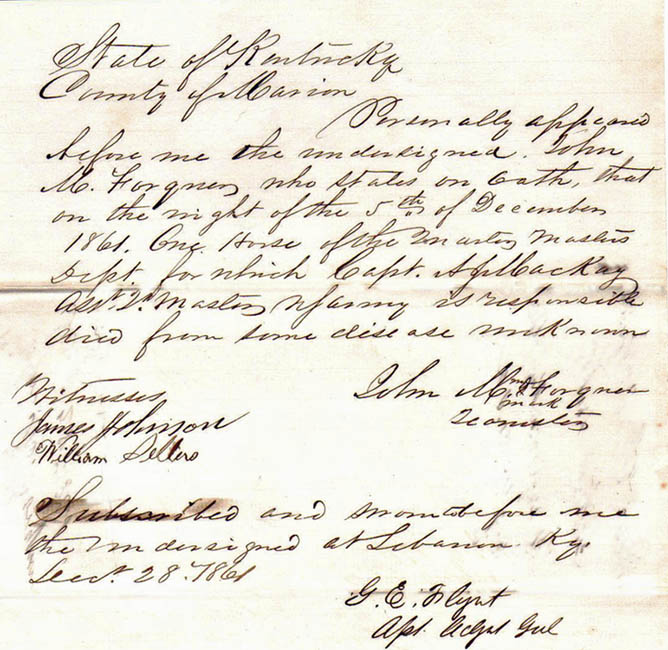

"died from some disease unknown"

The Civil War was hard on horses. This December 1861 document records the death of a horse that

was property of the Quartermaster Department. Those responsible for the horse wished

to document its death to avoid being charged with absconding with federal property.

|

It was not until 1855 that the U.S. Army created mounted units that were actually called cavalry. At the time of their creation they were distinct in being armed with Colt Navy pattern pistols, a new-fangled weapon for its time, but one that proved its worth during the Mexican War and on the frontier. By the outbreak of the Civil War the Regular Army had five mounted regiments: two each of dragoons and cavalry and one of mounted riflemen. In August 1861 it was decided to rename all these units as cavalry, numbered according to the seniority of the regiment. Once that was done the former 1st Dragoon Regiment became the 1st U.S. Cavalry, and what had been the First Cavalry Regiment became the 4th Cavalry.

During the American Civil War additional volunteer cavalry regiments were raised by the various states and mustered into federal service. While Congress authorized only six Regular U.S. Cavalry regiments the various states contributed some 272 cavalry regiments to the federal service. Early in the war the then Major General Commanding the Army Winfield Scott discouraged the formation and acceptance of cavalry. His logic was that training an effective cavalry unit took time and that the war would be short. However, the South accepted as many mounted units as its citizens formed and soon the need for cavalry in the North was recognized, and the policy reversed. For example, during the first battle of Bun Run there were only seven companies of Federal Cavalry on the field while the Confederates had one entire regiment, a four-company battalion, and several independent companies. The Confederate cavalry proved to be extremely effective and the First Virginia Cavalry, commanded by J. E. B. Stuart, attacked and helped rout the 11th New York Fire Zouaves, a unit that had been attempting to establish an elite reputation. They also pursued the retreating Union army and captured prisoners and needed material.

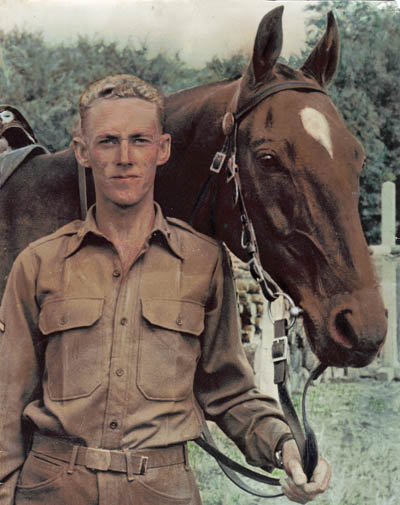

A Civil War Trooper and his Horse

|

|

Civil War Enlisted Hat Insignia

|

|

Early in the war Federal cavalry was judged not to have been the equals of the Confederates and was not used effectively. Stuart literally rode circles around the Union Army, frustrating the Union command and garnering a lot of publicity. However, what he achieved in the long run was a determination by his enemy to improve their cavalry arm, and by the 1863 Battle of Brandy Station it was Stuart who was surprised and given a bloody nose by the newly invigorated Union cavalry. Although the Confederates held the field and ultimately launched the Gettysburg campaign, the experience may have encouraged Stuart to try to regain his reputation with an over-extended raid that increasingly took him farther away from the main body of the Confederate Army of Robert E. Lee. His raid contributed to his ultimate failure to arrive on the battlefield in a timely manner and did little damage to the Union Army both materially or psychologically. When he did arrive he was checked by an equally aggressive (perhaps to the point of recklessness) Union cavalry leader in the person of George Armstrong Custer. Toward the end of the war the Union cavalry mounted destructive raids into southern territory, were armed with newly invented breach loading carbines that the industrial base of the South could not match and had perfected massive remount and veterinary capabilities that kept its troopers in the saddle and its artillery horses in their traces. The Confederate cavalry, on the other hand, was running out of horseflesh and found itself outnumbered and on the defensive. One can only wonder if Lee had had a better cavalry force available at the time of Appomattox might he have been able to slip away. However, the fate of the Confederacy was sealed before the first gun was fired, and the war would have ended with a Union victory so long as the northern population preserved the will to fight and had effective leadership.

So-Called Model 1860 Cavalry Saber

Sabers were still used during the Civil War.

|

A Spur Excavated from a Civil War Campsite.

|

|

Lock Plate from a Sharps Carbine

Breech loading weapons forever changed warfare.

|

|

Model 1863 Curb Bit Boss

|

|

During the Second World War tanks or assault guns were often rushed to the front and committed to combat with the paint barely dry so long as crews were available. This is not the case with cavalry mounts in the 19th Century. Immature and untrained horses are useless as cavalry mounts, and since wars last only so long they have to be fought with the existing inventory of animals. Combat, poor care, disease, stress, inadequate diet, lack of forage, hard road surfaces and carelessness all took their toll on horse flesh and the armies used up a large numbers of horses and mules. The price of animals steadily increased during the war, and there were standards written for purchasing agents of the quartermaster corps to follow in judging the fitness of the animals for service. The war did not distinguish between civilian and military horses either. Both armies often filched horses from civilians when operating in enemy territory. This was done both to supply the needs of the service but more important to deny their use to the enemy. At the end of the Civil War the Army sold its surplus of 104,000 horses at public auction.

A trooper of the 5th Cavalry

Indian War Period

|

|

With the end of the Civil War the United States embarked on a course of economic growth and westward expansion. In 1866 Congress authorized a total of 10 regiments of cavalry plus a corps of Indian Scouts. The 9th and the 10th Cavalry Regiments were composed of African-American soldiers and acquired the nickname of “Buffalo Soldiers.” In 1868 this force was scattered among some 59 outposts across the western states. Life was hard and conditions primitive. One cavalry officer commented in his memoirs that he never knew of any man, soldier or civilian, in the region who died a natural death. This was the period of the Indian Wars and cavalry units were employed were pursuing a foe who possessed a warrior ethos, superb horsemanship skills, superior knowledge of local conditions, and most surprisingly, often superior weapons purchased from white traders. The Indian tribes, despite their well-known successes such as the Fetterman Fight or the Little Bighorn, were as doomed as was the Confederacy to inevitable subjugation by sheer weight of numbers and persistence. The last act of hostility between Indian and soldier was the December 29, 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre which pitted the 7th Cavalry Regiment against a band of Lakota Sioux Indian including many women and children. Neither side was looking for a fight but a misunderstanding while the soldiers attempted to disarm the Indians touched off a fusillade of gunfire and the following massacre. It would be wrong to say that the Indians did not put up resistance or that soldiers did not die, but for the most part the characterization of the event as a massacre of Indians is accurate in that the soldiers fired on all the assembled Indians indiscriminately. Even the Army was uncomfortable with the events, and General Nelson Miles, commander of the Department of the Missouri, denounced the colonel of the 7th Cavalry and relieved him of command.

Service Medal for Indian Wars

|

|

|

After the close of the Indian Wars the cavalry arm languished. During the Spanish American War and the Philippine Insurrection cavalry units often fought as infantry. For example the Rough Riders of the First Volunteer Cavalry Regiment made their famous attack on San Juan Hill on foot. In 1916 a Mexican border incident, specifically the attack by the Mexican revolutionary leader often called a bandit, Francisco (Pancho) Villa on Columbus, New Mexico, caused the United States to launch a putative expedition into Mexico. In many ways this was the last major cavalry action of the United States Army in North America. On March 29, 1916 the 7th Cavalry fought an equal sized force of supporters of Villa at Guerrero, Mexico. Large numbers of National Guard troops were mobilized and sent to the border and the U.S. began to pay more attention to military matters. Two new Regular Army cavalry regiments, the 16th and 17th, were formed at the time.

7th Cavalry Collar Insignia

Early 20th Century

|

|

At the same time and farther from home, Europe was fighting the First World War. Eventually the United States was draw into the war as an ally of Britain and France. The reality of the war was that there was little role for cavalry units and many units were converted to field artillery. A provisional mounted squadron of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment was involved in courier, reconnaissance, liaison and military police duties and did see action against the enemy, but it was clear that there would be no more glamorous charges with bugles blaring and guidons flapping. Equally important the war saw extensive employment of motorized vehicles and the tank.

After the war ended there was reorganization of the cavalry branch. Many units were reduced to near skeletons. Cavalry officers and thought leaders looked for ways cavalry might be employed in modern war. You see quotes like the following, "We must not be misled....to assume that the untried machine can displace the proved and tried horse." (Major General John K. Herr, Chief of Cavalry 1938). At the same time the Tank Corps of World War One was abolished by Congress in 1920 and it would not be until nearly the end of the Second World War that the United States caught up to nations like Germany and Russia who more fully recognized the potential of modern armored warfare. Tanks were viewed as a supplement to infantry and the idea of highly mobile, focused concentrations of them being used strategically was foreign to the thinking of the older officers. Armored warfare had no strong voice at the highest levels of the army establishment until 1939 when the German successes in the opening campaigns of World War Two jolted planners out of their complacency.

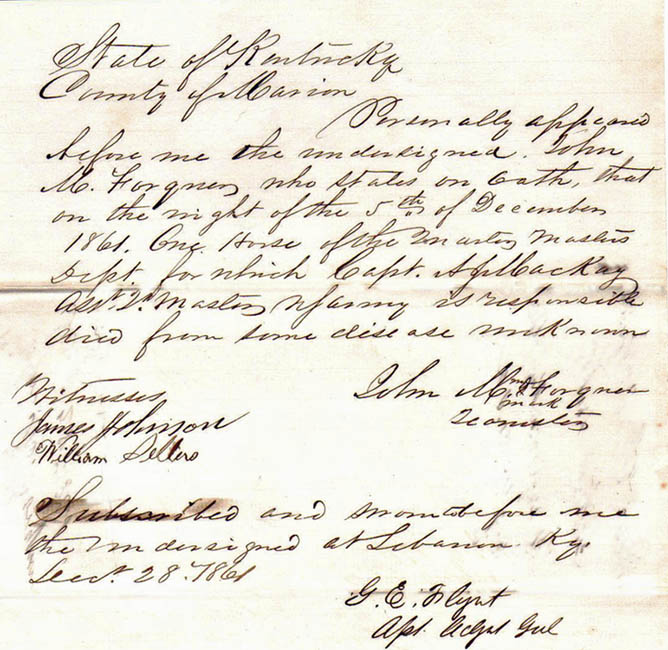

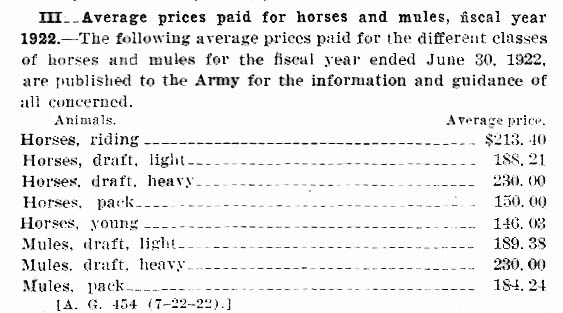

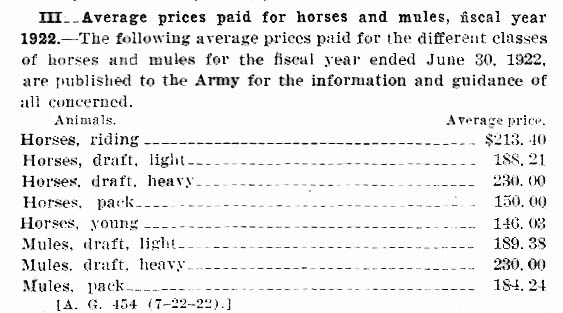

Prices Paid by Army for Horses and Mules 1922

|

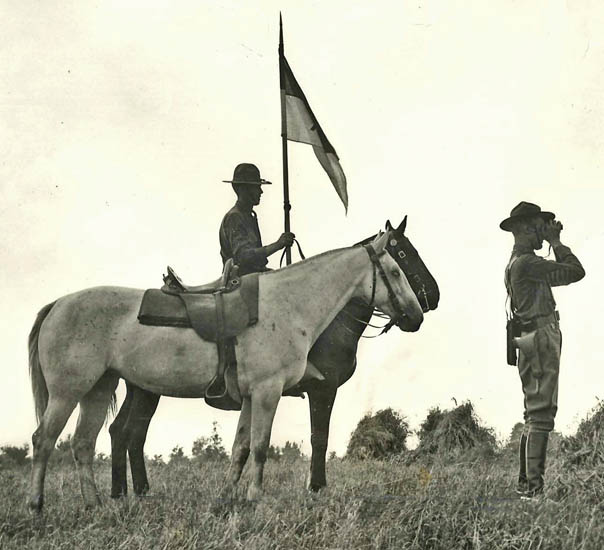

Two Fifth Cavalry Regiment Cavalrymen and their Mounts

Camp Pine, NY 1935

|

"Get A Horse" Camp Pine, N.Y.

Mechanization also had its limits.

|

|

Up in their Hocks in Mud, Camp Pine, N.Y.

The cavalry was not all glamor.

|

|

Lapel Insignia 10th Cavalry Officer

Pre-World War II period

|

|

|

This lack of interest in tanks and the budget restrictions of the depression provided a breather for the horse cavalry during the period between the First and the Second World Wars. However, movement toward mechanization was steady and came from the top. During Douglas MacArthur’s tenure as chief of staff he ordered units including cavalry to adopt mechanization and motorization as far as practical. Cavalry units experimented with portee transportation of horses, that is to say loading them in horse trailers and included motorized vehicles and armored cars in their tables of organization. One by one existing cavalry units were mechanized with the idea they were still performing a fundamental cavalry role of reconnaissance. In 1940 and 1941 the Army ordered a series of maneuvers and mock battles in New York and Louisiana. During these maneuvers the fate of horse cavalry was on the table. The horseman put in a spirited attempt to fulfill their missions but it the end the Army brass found them wanting. The office of chief of cavalry was discontinued on March 9, 1942. In 1943 the First Cavalry Division turned in its horses and fought the war as an infantry unit. The Second Cavalry Division, which included the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments of “Buffalo Soldiers,” fame was also dismounted and sent to North Africa where in March of 1944 these regiments with such proud traditions were inactivated and their personnel ignominiously transferred to engineer and port battalions. However, it was the 26th Cavalry Regiment, consisting mostly of Philippine Scouts, that was the last U.S. unit to engage in a horse-mounted attack. This charge occurred at the town of Morong in the Philippines Islands against the Japanese on January 16, 1942.

Model 1904 McClellan Pattern Cavalry Saddle

First used in 1857 these classic saddles remained

in service with modifications until the demise of horse cavalry.

|

Other nations have retained ceremonial mounted cavalry units, such as the Horse Guards in the United Kingdom, but the United States Army has chosen not to do that on a national level. This may be a legacy of the unsuccessful fight by the cavalry branch to hold onto its horses in the 1940s. It is somewhat ironic that those horses still used by the U.S. Army at Arlington National Cemetery are not part of a cavalry or artillery unit, which would have been their traditional home, but rather the Caisson Platoon of the Third Infantry Regiment. The First Cavalry Division does have a mounted detachment based at Fort Hood. Among the things they do is reenact Indian War Cavalry tactics. There are also mounted units that are a part of their state militia; for example, The First Company Governor's Horse Guard of Hartford, Connecticut. Here in Maryland we have a small, mounted ceremonial unit that is part of the Maryland Defense Force, known as "Troop A." During the two World Wars when National Guard units were mobilized and sent overseas, the states were authorized to organize a State Guard or Defense Force as distinct from the National Guard. These units were often comprised of older men and were limited to service only within their own state. The traditions of Troop A trace to a time when Maryland, a small state that could not field a full cavalry regiment, had its Troop A. For many years it was a National Guard unit stationed at the Pikesville National Guard Armory. In 1917 they boasted a total of 105 troopers but in more recent times the unit became defunct. Members of the modern Maryland Defense Force have resurrected the traditions of the unit and Maryland once again has a cavalry outfit. Members of the modern Troop A are full-fledged, voluntary members of a state military organization but are not subject to involuntary out-of-state deployment. They act as a mounted color guard and parade unit at various public functions.

U.S. Army units that serve in a mechanized reconnaissance or air mobile role still carry the designation of being cavalry. During the Iraq War the 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment performed its role brilliantly and in a lightning strike placed itself at the very center of Iraqi power in Baghdad. George Armstrong Custer, J.E.B. Stuart and Nathan B. Forrest would have approved and this action no doubt will be a teaching point at war colleges for years to come. What they did was the very essence of cavalry if not preformed using horses. The unit’s success caught both the Iraqis and our own command off balance and the speed at which the Iraqi government fell apart led to a breakdown of civil order in Baghdad that had the unintended consequence of damaging the reputations of those responsible at the highest levels for an overall successful operation. We learn much from success but even better lessons are caught by our failures. It is too bad that George Armstrong Custer never had the opportunity to learn anything from his own ultimate and spectacular failure at the Little Bighorn. One truth about warfare is that results are immediate and only too often there are no second chances.

First Company Governor's Horse Guard Officer's Lapel Insignia 1930s

|

First Cavalry Division Mounted Detachment 2005

Photo by Spc. Paula Taylor

|

All images are either public domain or from the author's collection.

More Information on Troop A Maryland Defense Force

Additional Information on Troop A Maryland Defense Force

Evolution of U.S. Army Cavalry Insignia

Twilight of the Horse Cavalry

Back to Discussions about Horse Related Topics

Back to Insignia of World War Two

Back to Uniforms of the Civil War