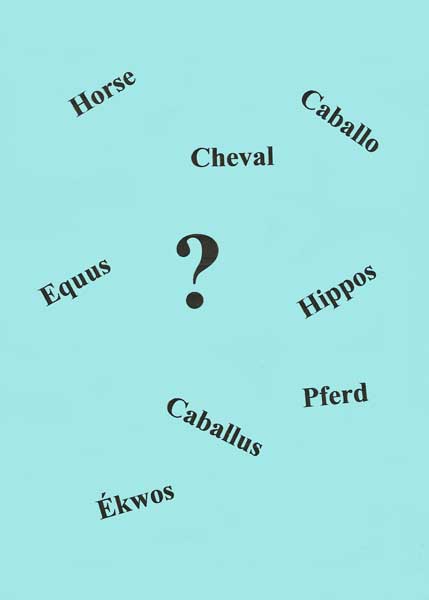

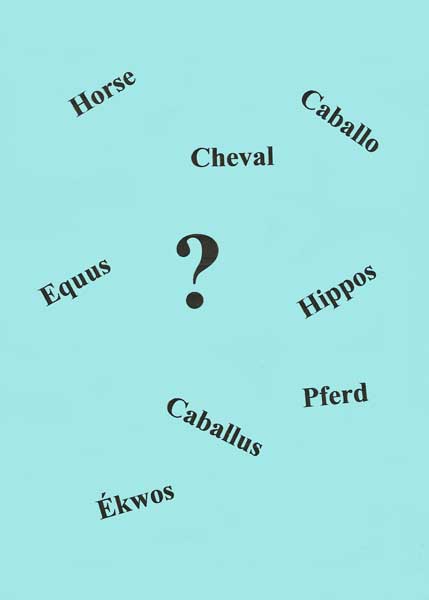

A Horse by Any Other Name:

The Origins of the Words for Horse in Various Languages

|

|

|

|

Human language is not constant and changes over time. Everything changes: pronunciations, word meanings and even grammar. Read Shakespeare or even listen to modern British TV shows (without closed captioning) and you will see what I mean. English is part of the broader Indo-European language family, a series of related languages believed to have a common prehistoric origin. That original language is lost, but a word list has been reconstructed for many common words.

The process of reconstruction of the original Indo-European language is somewhat similar to your taking photographs of everyone attending the family reunion and running the photographs through a computer program that averages and combines the photographs into a single face. The end result might just look a little like your great-great-grandfather and common ancestor of the group. This is a simplified explanation and language reconstruction also involves applying certain rules about how sounds in languages are likely to change over time. If you hear the word for horse in English and also in other familiar Indo-European languages, most of them sound very different, and you might think that this entire notion of an Indo-European language family is all wrong. However, there are explanations why this is true in the case of the various words that mean horse.

Scholars have reconstructed the original Proto-Indo-European word for horse as ékwos. This word slowly evolved into the Greek hippos and the Latin equus and many other words in various ancient languages. These classical roots are preserved in modern English words like “hippodrome” and “equestrian." However, the Romans used a second slang word (in Vulgar Latin or common spoken Latin) for horse caballus, which at the time had the connotation of being a nag. This word, and not the more formal Latin equus, became the word for horse in Romance languages that evolved from Latin. For example, we have caballo in Spanish and cheval in French.

The usually given German word for horse is Pferd, which sounds nothing like the words for horse in the Romance languages. However, this word originated from another Latin word paraveredus. This word originally had a very specific meaning of a spare post horse in a way station. No doubt the Germans who first had contact with the Roman Empire were aware of the Roman courier system, but just why they would borrow this specific word, generalize it to the class of all horses,and gave up their older word for horse is uncertain. No doubt the Roman stations where missing all of their fine paraveredi after the German tribes passed through. Paraveredus became palefridus and in time was shortened to Pfred. The word palefridus is the also the origin of the English word “palfrey.” There is a second German word for horse that was more commonly used in the southern regions of the country: das Ross. Like many regionalisms its use is in decline. The English word "horse" does not sound anything like the words of the other languages and in fact may be closer than Pferd to the original old German word. Its origin was a prehistoric Germanic word reconstructed as khorsaz. This word also evolved into the Icelandic word for horse hestur.

It seems odd that a word like ékwos evolved in over six thousand years of people talking into the word horse. The truth is that language change is all around us, and we hardly notice it. We say m-EYE-graines for migraines while the English say m-E-graines. We hear them say “His Majesty’s Clarks” (for his Majestie's Clerkes, a British a cappella group) while we would say it as “His Majesty’s Clerks.” For the most part this hits us as a momentary oddity, and we move on speaking our language as we heard learned it on our mother’s knee. However, what we are really hearing is that slow process of language change.

I am again, the ever curious,

Accidental Horseman