The Horse’s Eye

|

|

It might be natural to assume that a horse’s vision is much the same as our own. Vision is a paramount human sense, and we tend to believe our eyes when confronted by conflicting sensations. However, a horse’s eye is very different than that of a human in both design and function.

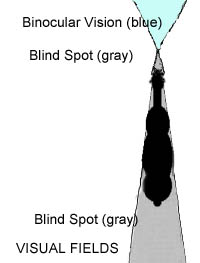

A very basic and obvious difference is the placement of the eyes on the face. Human eyes are placed forward on the face. Because of this we have very well developed binocular vision, accounted for by overlapping visual fields. If you look at a point in front of you and alternately cover and uncover each eye, you will see part of your visual field disappears. Our vision is most acute when we focus an object directly on the macular area of the retina. When we are seeing with only one eye we lose depth perception, but we may not be fully aware of it since the brain is good at organizing the environment based on our prior knowledge of it. One of our eyes is able to take in an arc about 60 degrees toward the nose and 100 degrees toward the temple.

|

There are other areas where the two species differ. Our pupils readily react to light; a horse’s eye does not. Horses are at a distinct disadvantage when there is a sudden change in the intensity of light. In their natural environment, which is open grassland, sudden dramatic changes in light are uncommon. However, in man-made structures, and with things such as light switches, or in darkened horse trailers, horses are often challenged by being asked to do things when they have been blinded by a sudden change in the level of illumination. If you look inside of the anterior chamber of a horse's eye you will see a structure known as the corpora nigra just above the pupil. It is visible in the above photograph. The purpose of the corpora nigra is to shade the pupil from glare. Another difference is that the lenses of horses’ eyes do not accommodate as well as those in humans. There are small muscles on the inside of the eye which bend the lens and focus objects on the light sensitive retina. Horses use a different strategy for focusing objects. The surface of the eye itself is set at different focal lengths such that when a horse has its eyes down and is grazing, near objects are in focus, and when a horse raises its head, far objects are in focus. This happens without the need to wait for the much larger equine lens to accommodate. This ability affords the horse some additional milliseconds of reaction time that might be the difference between falling prey to a predator and a successful escape.

|

It would be possible to design an optical system that would simulate for a human the visual experience of a horse, and I suspect that it would be both informative and somewhat disorienting for us. However, I do not know if anyone has taken the time and expense to do this. Our failure to appreciate the nature of a horse’s vision often leads to problems. Those dressage horses with an exaggerated tuck to their necks look rather grand in the ring but have been known to collide with each other while being schooled in a group because they are basically looking down at the ground and cannot see what is directly in front of them. There have been occasions when while trail riding I have had to warn my horse off from walking directly into a tree that was in his blind spot. Show riders have learned to allow their horses freedom of head movement so that they are capable of seeing the jump. Course designers have begun to take the nature of the horse’s color vision into account by designing jumps whose color characteristics contrast in such a way that the horse can clearly see them.

The differences between human and equine eyes were developed over millennia of natural selection. Humans are primates and developed as tree dwelling creatures. One false move and a primate took a tumble. Good color vision aided finding food. Superior vision was the key to survival in that world. For horses, visual needs were different. Having a huge visual field allowed them to detect approaching predators. Since predators are equally active night and day and since horses cannot really hide, good night vision was equally important. Since horses are specialized to eat green grass, color vision was not critical. The differences in vision between horses and men are all accounted for by the survival needs of the species. It would be wrong to say one is somehow better or worse. Both were well adapted to their natural environment. When working with horses we need to appreciate how they experience the world and understand that their experience is not the same as ours.