Photo:Christopher Dydyk

|

Most of the horses that I have owned and ridden were pre-owned and came to me already started by someone else. However, we did start my gray gelding, and I was surprised that it was not nearly as difficult as I imagined. Because we had cared for him since he was weaned, he knew us and trusted us. He was cooperative and seemed more puzzled by the process than resistant or upset. In slow, easy steps he accepted the bit, saddle and rider. We did not use Monty Roberts’ method, and I am uncertain if I even knew of it at the time.

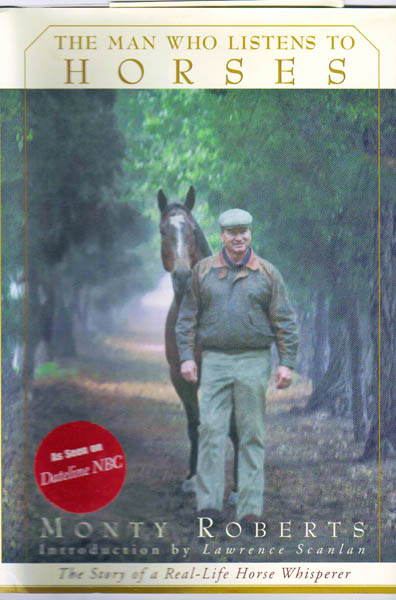

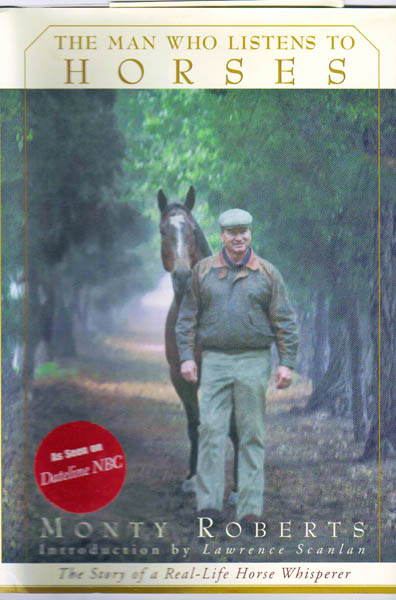

When you watch Monty Roberts explaining the technique, some of the things he says seem counter-intuitive. However, basically what he is doing is pushing certain behavioral buttons that nature has built into the horse’s normal behavior. Those behaviors have to do with two different areas that are hardwired into a horse’s psyche. For the most part the technique is dependent on the facets of herding instinct and inter-herd behavior. To a much lesser extent it is also based on certain aspects of predator-prey interaction.

Roberts’ technique is first to pressure the horse to flee from him. A horse is a prey and flight animal. Their first reaction is to flee from novel situations that might indicate danger. In his demonstrations, Roberts uses a round pen and the horse soon discovers that he is fleeing in circles, and this person is not going away. There is only so much running and then the horse asks itself if there might be an easier way. Worse than that, the horse is alone in this situation. There is no herd to watch his back or give solace to him. At this point Roberts changes tactic and takes the pressure off. He invites the horse to join his herd, and soon the horse is following him around. What the horse discovers is by doing this Roberts takes the pressure off. Roberts describes how the lead mare of a herd behaves in the same way with an unruly colt. She first drives him off and then accepts him back on her terms. These are facets of herd behavior and things that the horse has experienced before. Join up is not particularly a facet of predator-prey interaction. There is no negotiating or joining up with a predator; it is interested only in a meal.

Among the signs Roberts looks for is a “licking and chewing” action of the horse’s month. I view this as an indicator that the animal is acknowledging that it is submissive to the trainer. It is the equine version of the Chinese kowtow or European bowing. The first time I noticed this was when we introduced my gray to the herd as a weanling. The other horses were aggressive toward him in an effort to establish their dominance, and he responded with this “licking and chewing” action. Clearly, this is a hardwired equine behavioral response that is recognized by other horses as saying, “I am just a baby and am not challenging you, so leave me alone.” Roberts explains this a little differently, but I like my explanation better. Roberts talks about horses having a language, a means of communicating with each other, that he calls “Equus.” This makes perfect sense. Any herd or social animal needs ways to communicate with its fellows and will tend to evolve a social hierarchy. Complex social behaviors exist in flocks of wild turkeys, wolf packs and any other cooperating group of animals that you might care to observe. It is no surprise that such communication behaviors exist among a herd of horses.

Perhaps, the most counter-intuitive behavioral feature he discussed is what he calls “advance and retreat.” A horse will retreat from a threat initially and then later reapproach it. I think if I were a horse facing a predator that I would rather be in the next county and not circling back toward it. However, the advance and retreat strategy may make sense. Most predators are ambush predators and if a prey animal keeps it in its sight, it is much less dangerous than if the prey loses sight of it, and the predator can launch a future undetected attack. I have noticed deer herds doing this. They will run a distance and then turn and stand and look at you.

|

|