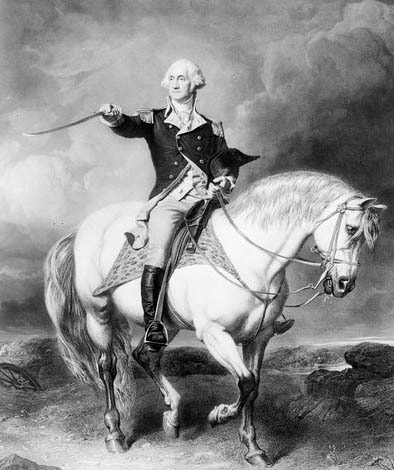

Presidents and Horses:

George Washington and Horses Blueskin and Nelson

|

|

George Washington (February 22, 1732 [old calendar February 11, 1731] – December 14, 1799) was the first President of the United States. Henry Lee said of Washington, “First in war, first in peace and first in the hearts of his countrymen.” It is also said by no less than Thomas Jefferson that Washington was, “the best horseman of his age.” Jefferson himself is reported to cut have a good figure on horseback and to have owned fine animals, so the compliment may be more than hyperbole. Jefferson would have known a good horseman when he saw one, particularly during an age when being an accomplished horseman was taken as a mark of a true gentleman.

Washington’s ability as a horseman had historical significance. During the Revolutionary War the revolting colonies lacked legitimacy both in the eyes of the world and that of the mother county. The British leadership was prepared to dismiss the rebels as a mob comprised of persons of no account and certainly not gentlemen of breeding. However, there for all to see was Washington, a man refused to conform to their prejudices. Those British officers who met with Washington under flags of truce all testified that he was a very impressive figure, both on horseback and off. Washington’s persona as a true gentleman and a heroic leader had a profound psychological effect on both his friends and enemies. It is also true that in an era when a commander utilized the mobility of a horse to monitor the progress of military operations, being a good horseman had its practical applications.

George Washington’s horsemanship was no accident. It was honed on the hunt fields of Virginia, where he was an avid fox hunter. Washington’s diary confirms that it was not unusual to hunt for seven or eight hours at a time. It seems that Washington was a true enthusiast, riding close on the hounds, leaping fences and moving as fast as possible. His favorite hunter was Blueskin; a horse that during its youth had a dark iron-gray, almost blue, coat. Blueskin was a spirited animal, known for his endurance during a long chase. Washington took Blueskin to war and later retired him to Mount Vernon.

Another horse closely identified with Washington was his chestnut horse, Nelson. Nelson, who bore the stable name "Old Onzie", was a gift from Thomas Nelson, Jr. (1738-1789), a signer of the Declaration of Independence and later governor of Virginia. Nelson was 16-hands tall with white face and legs. Washington received Nelson in 1778 and renamed him for his donor. After the war Nelson was also retired to Mount Vernon where he was affectionately cared for until his 1790 death.

Washington was not the only man from his household who was an avid hunter. He was accompanied on hunts by William "Billy" Lee (1750–1828), his sometimes huntsman and body servant (the polite term of the period for one who was a slave). Billy Lee was said to be every bit as accomplished and fearless a rider as Washington. Lee went to war with his master and appears at Washington’s side in John Trumbull's 1780 painting. William Lee became a freeman under provisions of Washington’s will.

Washington's step-grandson George Washington Parke Custis (1781–1857) left an account of William Lee,

“Will, the huntsman, better known in Revolutionary lore as Billy, rode a horse called Chinkling, a surprising leaper, and made very much like its rider, low, but sturdy, and of great bone and muscle. Will had but one order, which was to keep with the hounds; and, mounted on Chinkling ... this fearless horseman would rush, at full speed, through brake or tangled wood, in a style at which modern huntsmen would stand aghast.”

Not only was Washington an avid fox hunter, he was also a breeder of fox hounds and established the American breed of fox hounds by crossing those originally brought from England with those the Marquis de Lafayette sent him from France as a gift.

Wellington’s famous quote, "The battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton" was probably apocryphal. However, might it be said that the American Revolution was won on the hunt fields of Virginia? I am posing this question for serious consideration.

Great physical endurance is required of soldiers, but they are only flesh and blood men. After conducting the brilliant and demanding Valley Campaign, the exhausted Stonewall Jackson fell into a deep sleep in broad daylight and while conducting a critical phase of the following Seven-Days Campaign. The unfortunate (for the South) results of his somnolence became one of many “what ifs” of the American Civil War and only one of many examples where exhaustion has affected history. George Washington was known for a strong constitution and exceptional physical and mental endurance that were developed originally on the hunt field. Equally important was his tenacity, the result of staying with the hounds no matter what. Hunting is not for the faint of heart, and Washington was equally courageous in battle. A good hunter is aggressive in pursuit and Washington more than once with his rag tag army turned the tables on the British, with moves as sly as the fox he once hunted.

Of course, fox hunting was not the sole influence on Washington’s character, no more than Wellington’s abilities were solely the result of whatever he was doing on the playing fields of Eton. Notwithstanding, I would argue that had Washington not been the man he was that history have played out very differently and you, my friend, might now be singing “God save the Queen” with a fervor equal to our British cousins.

Yours truly,